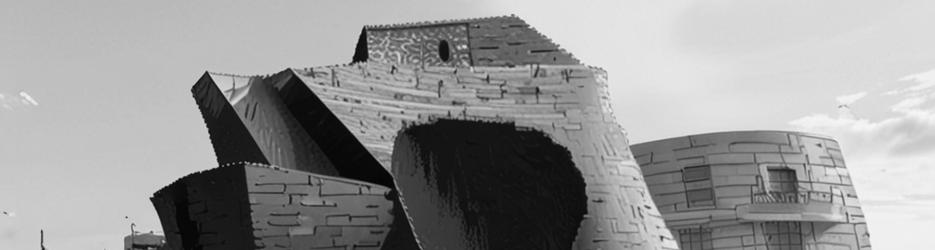

Museums like Bilbao’s Guggenheim enchant and enrich their host cities, attracting visitors from around the globe while injecting new life into the economy. So when it comes to a new vision for the city, what can Perth learn from The Bilbao Effect?

Question: how do you turn a second-tier city, or one in serious decline, into an international tourism destination? Answer: build an art museum and fill it with cutting-edge contemporary art.

Following the huge success of the Guggenheim Museum, which opened in the small Basque town of Bilbao in the north of Spain in 1997, the world was introduced to a new phenomenon branded The Bilbao Effect. Many cities around the world have embraced this as the answer to their prayers, and opened their arms and their wallets to famous architects to build them an art museum.

Of course, this isn't entirely new, important cities have been defined by their architecture for millennia – you only have to think of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus, the Lighthouse of Alexandria, the Parthenon in Athens, the Forbidden City in Beijing, or even the Empire State Building in New York. These works of architecture have been important in framing the identities of their host cities and their inhabitants, and in attracting visitors to stand in awe and experience the thrill of their first encounter. But in Bilbao there wasn't much else that was impressive, and certainly nothing else to attract an international audience. Hobart has enjoyed a similar upsurge of tourism following the opening of the Museum of Old and New Art (MONA) in 2011. The Bilbao Effect must seem like a gift: build it and they will come.

.jpg)

The Matter of Time by Richard Serra, Guggenheim Museum Bilbao.

Despite the costs – and they are significant – both MONA and the Guggenheim Bilbao have shown that building an adventurously designed museum and filling it with challenging contemporary art can dramatically increase tourist visitation and boost the economy in ways that few other initiatives can achieve.

When the Bilbao City Council decided to spend US$120 million in a partnership with the Guggenheim Museum in New York to create a new museum in their town, it offered the commission to famous American architect Frank Gehry. Although the budget almost doubled to US$228.3 million before the museum opened, Gehry's fantastical building generated a new descriptor, Destination Architecture – it drew people to this small, nondescript town simply through the fact of its existence. A visitor survey has revealed that 82 per cent of tourists go to the city of Bilbao exclusively to see the museum, or extend their stay to accommodate a visit. In the museum's first 10 years of operation, this translated to roughly 800,000 overnight stays a year (compared to fewer than 100,000 before the museum opened), contributing approximately US$200 million annually to the community and US$40 million in taxes to the Basque Treasury. The museum has also directly or indirectly created almost 1000 new jobs in a city where employment was in severe decline.

Why was it so successful? Well, arriving at the plaza by the river is one of the great travel experiences.

Shooting up above you in all directions, and twisting and spiralling with giddy abandon, the museum is breathtaking. Its shimmering skin is grey one moment, and sparkling gold the next, as it catches the late afternoon sun. It seems to have no boundaries: it pulsates and then morphs into new shapes as you move around its sinuous curves. Nothing can prepare you for that first encounter, the sight of this tumble of titanium, soaring up and engulfing the riverbank – not the millions of amateur photographs on the internet, nor the documentaries or books on Gehry's work. It must be experienced first-hand.

Sucked down into its interior via the entrance corridor, the building continues to enthrall and bemuse as twisting forms and cantilevered arches spin above

your head in a continuous scrolling that keeps you moving round and round to catch every detail. Inside, the artwork is equally awe-inspiring.

(1).jpg)

.jpg)

MONA has become Hobart's second most popular tourist spot, thanks to its appealing design and quirky exhibits, like the Mickey Mouse stools (above).

Richard Serra's The Matter of Time (1994–2005) is a permanent installation comprised of seven commissioned works and his earlier piece Snake (1994–1997), located in the vast major hall of the museum and filling it with ease. As you move through and around these rusty walls of Corten steel, precariously tilting and threatening collapse, it is hard to imagine life outside the museum, where days are measured by routine and safe consistency. Here, all is at risk – everything is in flux and all your senses are heightened.

Although right angles and straight lines are banished from the building's exterior and the major circulation areas, the interior features gallery spaces with clean, crisp lines and flat walls, ideal for the changing selection of works from the Guggenheim in New York and the regular exhibitions of contemporary work from around the world. Presented within this uniquely honed architectural space, as demanding on your attention as the artworks themselves, the Bilbao experience is enthralling.

In answer to the obvious question – 'Would people come if the building were simply a white modernist box?' – the answer is 'Probably not', but the combination of elements — the wonderful installations, external works like Jeff Koons' Puppy, the collection's works and the special exhibitions — creates an irresistible tourist magnet.

.jpg)

Hobart's Museum of Old and New Art is another example of how

a beautifully designed cultural attraction can revitalise a region.

At the other end of the world, David Walsh's Museum of Old and New Art at Glenorchy, in an outer suburb of Hobart, has had a similar impact on the economy. Tourism Tasmania reports that, in its first year of operation, Walsh's $175 million museum became the second most popular site in Hobart, behind Salamanca Markets, with more than 400,000 people trooping through the doors in 2012. Altogether tourism contributed $1.46 billion to the local economy in that year, and the flow of visitors has increased over the intervening two years, spurred on by more and more challenging exhibitions, and the Dark MOFO and MONA FOMA music and art festivals.

When you arrive on the MONA ROMA Ferry — David Walsh's recommended means of accessing his museum — and pull into the jetty he built out into the bay, the museum towers above you. The extraordinary buttressing of Nonda Katsalidis' concrete and steel museum redefines the geography of the Berriedale peninsular on which it is built. Working within the seemingly impossible restrictions of building a vast public museum on a site with heritage-protected homes designed by feted architect Roy Grounds, the architect and client decided to cut into the hillside and build the museum underneath the protected buildings. The grand architectural sweep they initially proposed had to be reconsidered, and the site was stripped back to a bare rock face that dominates the interior of the building. The topography of the cliff has been completely re-ordered, and the two houses float above visitors' heads as they enter the underground galleries.

.jpg)

More than 400,000 people visited MONA in 2012 alone.

The museum houses Walsh's private collection, which is remarkable. Like the works at Bilbao, the artworks Walsh has put together contribute to the sense of excitement, to the edginess and the thrill of the MONA visitor experience. Everyone who visits has their must-tell-you-about favourite, whether it's the Cloaca Professional, 2010 by Belgian artist Wim Delvoye that replicates human digestion and excretion, producing faeces regularly at two o'clock each afternoon (not to be missed), or the wall of cast vaginas by Greg Taylor and Friends, Cunts ... and Other Conversations (2008-09). Equally popular are the real and virtual versions of the Pausiris mummy in its actual and digital sarcophagi, and the massive Sidney Nolan installation of paintings that together create the image of a snake occupying 46m of purpose-built gallery wall. They wouldn't be the same in a less inspiring building sited in an urban environment – at MONA, the dark labyrinthine galleries, the twisting steel stairwells and the soaring height and rough-hewn walls are an integral part of the process of engagement with the artworks.

Clearly these two museums have made a radical difference in enhancing the international profiles for their host cities, so what lessons can be learned for those involved in the redevelopment of Perth City? One of the facts that is rarely mentioned when discussing The Bilbao Effect is that the Guggenheim Museum was part of an holistic plan that included a new subway line, drainage and environmental clean-up systems, an airport, leisure and business complexes, and the relocation of other less attractive facilities to the outskirts of the city. Factoring in the provision of cultural investments within the larger planning envelope is a strategy that is more likely to achieve the desired results than simply building one museum.

.jpg)

Snake, by Sidney Nolan, features impressively at Bilbao's Guggenheim.

Most importantly, though, any cultural hub needs a vision it can offer to prospective audiences. The Western Australian Museum is rebranding itself as a museum of the Indian Ocean, which will not only showcase the extraordinary landscape and culture of this place but also open a conversation with those inhabiting the ocean that links us, revealing their treasures at the same time. As well as partnerships with the British Museum, the WAM is also planning exhibitions in collaboration with museums in Mumbai, Muscat, Abu Dhabi and Nairobi. The proposed Australian Aboriginal Cultures Museum at the University of Western Australia also aims to foster global understanding, and respect and appreciation of Aboriginal culture through the creation of a world-class museum that will showcase one of the world's finest collections of Aboriginal cultural material. The building, designed by Kerry Hill, will present exhibitions that will promote collaborative understanding and house the infrastructure that will conserve Aboriginal heritage.

As Bilbao and Hobart have shown, it is possible to create Destination Architecture that can house significant cultural materials, that will attract audiences and positively impact on the economic future of the host city. It is possible, but it requires a long-term commitment, buy-in from all political parties, and a coordinated and holistic plan. The new museum in Northbridge and the new Australian Aboriginal Cultures Museum at the University of Western Australia can become architectural attractions that will draw international audiences to engage with their collections. Better still, they may combine to form a hub of culturally significant buildings that will include the proposed cultural facilities planned for Elizabeth Quay. Vision and confidence built the new museums at Bilbao and Hobart, and those ingredients will also determine the success of the same in Perth.

.jpg)

Loop System Quintet, Conrad Shawcross, exhibited at MONA.