Covering almost half of WA, the Outback, along with the Amazon basin, is amongst a handful of intact wilderness areas remaining on earth.

Covering almost half of WA, the Outback, along with the Amazon basin, is amongst a handful of intact wilderness areas remaining on earth. But leading environmental campaigner Dr Barry Traill says this unspoiled place is suffering from the last problem anyone would expect: too few people...

Legend tells us that the Australian Outback is red, vast and barely inhabited. But it's also astonishingly varied, with sand dunes, mulga and desert waterholes, along with vast savannahs of palms, lush green floodplains, and fringes of dense mangrove forests.

The concept of the Outback has sometimes been deliberately and delightfully vague. In Australian myth-making, our storytellers, songwriters and poets often seek to establish the Outback as somewhere else, somewhere more remote, never quite exactly here or there. The residents are frequently described in terms tinged with nostalgia, its stockmen and Aboriginal people somehow from a time past, and not related to the modern world.

But the Outback is more than an idea. It is a tangible piece of Australia with real people living in its spaces. It covers an enormous swathe of land – more than 70 per cent of the continent – composed of the arid country of the centre and

west, and the tropical savannahs, wetlands and rain forests of the north. Just over 40 per cent of the Outback is in Western Australia, covering 2.2 million square kilometres.

Few countries can offer the gift of wide-open natural landscapes that are likely to remain strongholds for wildlife. In the first comprehensive study of the Outback as a whole, The Modern Outback: Nature, People and the Future of Remote Australia, The Pew Charitable Trusts identified the great natural places remaining on Earth, including the wild lands of the Amazon basin, the boreal forests and tundra of far northern North America, and the Australian Outback.

But on an increasingly crowded planet, the Outback's intact nature hides an apparently perverse problem: not too many people, but too few. Much of the region needs more people actively managing the land, to thwart deeply entrenched threats and keep the Outback's ecosystems thriving.

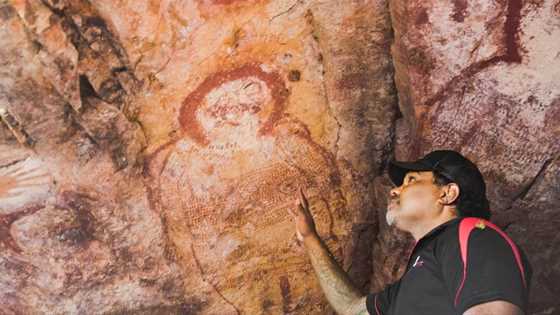

The Outback needs fire. Practices varied from place to place, but Aboriginal clans historically burned drier parts of the Outback in particular, often in nuanced ways. By setting smaller fires, they controlled vegetation growth by creating a patchwork of bush plants of different ages. Without the human hand, uncontrolled wildfires now burn intensely over huge areas of the deserts and savannahs, compromising the environment by removing food and habitat crucial for the survival of indigenous animals such as the bilby, Gouldian finch and dozens of other species.

A more recent threat came from the partner colonists of Europeans – feral animals. As in the rest of the country, the WA Outback now has feral cattle, pigs, donkeys, horses, camels, rabbits and goats, that eat native plants. Feral cats and foxes hunt small native animals, which are ill-adapted to deal with these relatively new predators.

Patchy social and economic foundations present unique challenges to the Outback and its residents. For example, many of the laws governing land use were created in the early 20th century and do not address the needs of the modern Outback. Meeting these challenges depends, to a large degree, on the condition of the land, which underpins much of the key enterprises of the region – tourism, pastoralism, fishing and emerging enterprises such as carbon farming.

We know now that to keep that land healthy throughout the Outback, we need to manage fire, control feral animals and noxious weeds, and put in place conservation and management programs that maintain nature and protect the general health of the environment.

Over the past 150 years, government policies and changing economic circumstances and priorities have resulted in an altered pattern of people living on the land. Much of the WA Outback has fewer people inhabiting and actively managing the millions of square kilometres than at any time over the past 50,000 years.

More can be done to provide a foundation for people to stay on the land and make a living. WA's pastoral leasehold arrangements, which cover much of the state, fail to encourage new enterprises and opportunities. More support is needed in the Outback for Indigenous Protected Areas (parks on Aboriginal lands), and National Parks.

The Outback is our birthright, and with that comes a responsibility as caretakers. This remote land is a deep part of our identity; it offers wide-open space far from suburban life that we can choose to visit or even reside in for a year, or a lifetime.

The modern Outback must move forward with values that respect nature and protect the land's communities and wildlife. Those best placed to lead this are the people who live in, value and actively care for the immense landscape. Connecting, supporting and resourcing these residents, Indigenous and non-Indigenous, provides the best chance we have to protect our island-continent's largest natural wonder for forever more.

This is an extract of the inaugural paper in a new series, The Outback Papers, published by The Pew Charitable Trusts. pewtrusts.org.au/outback. Dr. Barry Traill directs Pew's Outback Australia program.