That girl you’ve been eyeing up for the last ten minutes? What if she used to be a guy? We talk to members of Perth’s trans community about the blurring lines between sex and gender.

For most, gender is a fact. We mark the ‘male’ or ‘female’ box on forms at banks as automatically as the teller machine spits out cash; we use it as our most rudimentary way of defining the people around us: “That guy in the blue T-shirt”; “This girl I went to school with”. But for people with gender dysphoria – the persistent distress caused by the feeling of being born in the wrong gender – it’s not so simple.

For most of us, gender dysphoria is a difficult concept to grasp. Try imagining what it would feel like if unexpected genitals started sprouting from your body and you couldn’t stop it, and you get close to the feeling. But the analogy is insubstantial at best, because, simply, most of us have never not taken our gender for granted.

It’s time to start scribbling outside the boxes. Last year, in a victory for the trans community, the High Court of Australia unanimously ruled in favour of recognising a third gender category, ‘non-specific’, after a long-waged battle with the NSW Registrar of Births, Deaths and Marriages. On the last count, Facebook offered 71 gender options for UK users, with variants like polygender, androgyne, and two-spirit person (Australian drop-down menus still have a paltry two options). In May, a Time cover featuring Laverne Cox, the transgender star of the Netflix series Orange is the New Black proclaimed ‘The Transgender Tipping Point’, while the media speculates relentlessly on the gender identity of ex-Olympian Bruce Jenner, who’s been at the fore of pop culture through his ties with the Kardashians. The Royal Children’s Hospital Centre in Melbourne, the only clinic for transgender young people in Australia, has had an unprecedented 60-fold increase in referrals from 2003 to 2014. Frankly, binary gender has never looked so two-dimensional.

That’s not to claim it’s a modern zeitgeist. We’d need a book to go into it properly (Susan Stryker’s A Hundred Years of Transgender History is excellent), but the story of transgenderism is long and varied. In ancient Okinawa, some shamans underwent winagu nati, a process of ‘becoming female’. Many Native American tribes had third-gender roles, like ‘berdaches’, biological males who adopted traditional feminine roles, and ‘passing women’, assigned females who acted in masculine roles (these folk, incidentally, would’ve chosen ‘two-spirit person’ for their Facebook profile). In ancient Europe, male-to-female priestesses served Hecate, Diana and Artemis. Plato’s Symposium mentions androgynes, while the ancient – but still frequently thumbed – Kama Sutra references a third sex. No, not that kind.

When we talk about a person’s sex we’re referring to their biology – the collection of chromosomes and hormones determined in the womb. Gender is something a little different – okay, a lot different -; and a little more intangible. It’s a social construct; a psychology; an inherent sense of whether one is male, female, or something in between. It’s nothing to do with sexuality, either – a common misconception. One can be attracted to men, women, both or neither, regardless of one’s orientation.

While it’s usual for young kids to experiment with gender-bending (your daughter’s penchant for action figures; that little boy who dresses in fairy wings) if they hit puberty and still identify as a different gender to their biological sex, a staggering 99.5 per cent will continue to do so for the rest of their lives. That’s not a misprint.

“We think it’s a biological thing,” explains Dr Michelle Telfer, the leading clinician at the Royal Children’s Hospital Centre for Adolescent Health. “Just like if you’re lesbian or gay – it’s just who you are. In early childhood, gender can be a bit more fluid and people can identify various ways, but once puberty hits we know it’s very much a stable entity.”

At the Royal Children’s Hospital, children who identify as transgender and pass a rigorous assessment – which involves parental approval, two independent psychiatric opinions, and appraisal by a pediatrician – are offered puberty blockers, a way to pause sexual development.

“It allows the person time to develop socially and emotionally and think about whether or not they want to embark on the more permanent treatment that has changes that are not reversible,” says Dr Telfer. “As puberty progresses it obviously causes a lot of distress, like the growing of the breasts or the deepening of the larynx. [Puberty blockers] let people make decisions without the anxiety their body is developing in the way they don’t want it to.”

At the average age of about sixteen, one has to make the decision whether to press play or to change the channel. Those who choose to proceed with gender reassignment then start stage two – hormone replacement therapy – which involves the administering of oestrogen or testosterone. “We need to make sure that we’re certainly using those medications on the right individuals because the changes induced by those drugs are mostly irreversible,” says Dr. Telfer. “So, for example, if you identify as female and you start taking oestrogen, you’ll grow breasts. If you regret doing that, you can’t undo it. We have to be really careful about who we start on medication. That risk is very small but it is a risk, so we make sure we do a very thorough assessment process.”

People can also elect to undergo sex reassignment surgery, which involves genital reconstruction and sometimes ancillary procedures, like breast augmentations, chest reconstructions, mastectomies, and facial feminisation or masculinisation. And yes, we know what you’re wondering: You can still feel sensation and orgasm post-procedure. It’s important to note someone can be transgender and not have sex reassignment surgery, or even hormone therapy. For them, experiencing their proper gender may be expressed simply by the way they dress, or just the way they feel.

In the case of young people particularly, deciding when (or if) to undergo these procedures can be an ethical nightmare. But, when you consider the prevalence of self-harm among people with untreated gender dysphoria, the shades of grey suddenly look pretty stark.

According to Dr Telfer, more than 50 per cent of adolescents with gender dysphoria self-harm, and somewhere between 30 and 50 per cent of transgender adolescents attempt suicide – with some studies indicating an even higher figure.

“It’s a huge concern for us, but we do know that the rate of self-harm and suicide come down dramatically when one has access to support and medical treatment to change the body to align more with one’s gender,”

Matt Tilley, a Clinical Professional Fellow in the Department of Sexology at Curtin University, agrees. He has been part of the first Australian national study on trans mental health, partnered by Curtin and UWA and funded by the national depression initiative Beyond Blue. The study revealed 54.2 per cent of its participants had been diagnosed with clinical depression within the previous twelve months, and 62 per cent had been diagnosed with clinical anxiety over the same period. “We very much agree with puberty blockers for young kids, as long as they’ve been adequately assessed because it can reduce some of the need for gender reassignment surgery procedures later,” he says. “Those procedures are not only extremely expensive and possibly very painful but they’re also very difficult to access in Australia. Our research shows individuals who had begun to access hormones or gender reassignment surgery had a much greater quality of life more broadly, so they’re much less likely to experience anxiety or depression.”

According to Tilley, it’s important to note the “extreme” figures from the study don’t betray anything about transgenderism itself. They relate to the negative responses of other people in the community to trans people – transphobia. While this includes instances of social exclusion and violence, some of the most difficult aspects of the trans experience are subtler, like accessing healthcare services, or the legal barriers associated with changing identifying documents.

“We found that participants would report going to the doctor after going through medical procedures, and the receptionist would call them out into the room using their previous name,” says Tilley. “So Barry stands up, but Barry doesn’t look like Barry anymore. She looks how she truly feels she is – her name’s now Bernice. There’s this disparity. It’s not deliberate – it’s coming out of a lack of understanding.”

“We have a lot of recommendations in our report to mitigate these basic-level admin issues, but really it’s around state and territory government simplifying and creating consistent procedures throughout Australia for individuals to change their legal sex. We would also be clear medical intervention should not be a prerequisite for an individual to change their legal gender.”

“WA’s laws definitely need updating – equal opportunity discrimination protection laws really, really need to be reformed,” says Aram Hosie, 32, a transgender policy worker (and, incidentally, the partner of former senator Louise Pratt, with whom he is expecting a baby later this year). “They only offer discrimination protection if you’ve been able to change all your legal documentation. So what that means is, when you’re in the process of transitioning – which can actually be the time you’re most discriminated against – you have no discrimination protection.” WA is the only Australian state to not offer discrimination protection to transitioning people.

It can also be difficult for people to legally change gender because while the federal government deals with some legal documents, like passports, the state government controls others, like birth certificates. Each state decides its own rules, so things can get really murky. Like the rest of the states, WA law stipulates a person must have undergone some form of surgical intervention to change their sex on their birth certificate but makes the process harder with the need to apply for a gender recognition certificate (the only state apart from South Australia to do so). “Many people have surgery but lots of people don’t – it could be for medical reasons, or for financial reasons, or just they don’t want or need it,” says Aram. “Our law also says that to change sex you can’t be married, because they’re paranoid about accidentally creating a same-sex marriage. So if you’re in the circumstance of already being married with a partner, and later in your life you decide to transition – and your marriage survives the transition, which is a pretty big deal in itself – you’re then in the position of either going through life not having your sex recognised legally, or having to divorce your partner. Our gender recognition laws need to be changed so we’re not forcing people to get divorced and we’re not forcing people to get surgery.”

Everyone I interviewed stressed there’s a simple solution to gender confusion (yours, not theirs) – education. Services like the Freedom Centre and Perth Inner City Youth Services (PICYS) – a free holistic support service based in Leederville – are currently providing support and education to trans people and their families. “PICYS did counselling sessions between my parents and me, and really put my parents at ease, I was really lucky I had access to that service,” says trans woman Samantha. “They are exceptional.”

WA’s trans education is set to go up a few grades this year, with the introduction of the Safe Schools Coalition, promoting safety and inclusivity for gender-diverse students. “The program will work closely with school staff but also the child and the child’s family,” says Sally Richardson, National Program Director of Safe Schools Coalition. “They’ll implement a management plan, and that’s put in place by the young person in the family. They really take the guidance from the young person about their transition – who they’d like to tell when they’d like it to happen.”

If we didn’t start planning the colour of a baby’s room from the second we see a peanut-sized shape on an ultrasound if the aisles in toy stores weren’t as clearly demarcated as the Apartheid system, would gender dysphoria still exist?

“It’s an interesting question,” muses Dr. Telfer. “We look at the people coming to our clinics, and there’s a big peak in people when they start primary school. Primary school is a very gendered place – girls’ toilets, boys’ toilets, uniforms – so we notice that when we put the children into gendered environments it causes a lot of distress.”

“If we had a world that wasn’t gendered at all… Probably not,” says Dr. Telfer. “But I don’t know that’s ever going to happen.

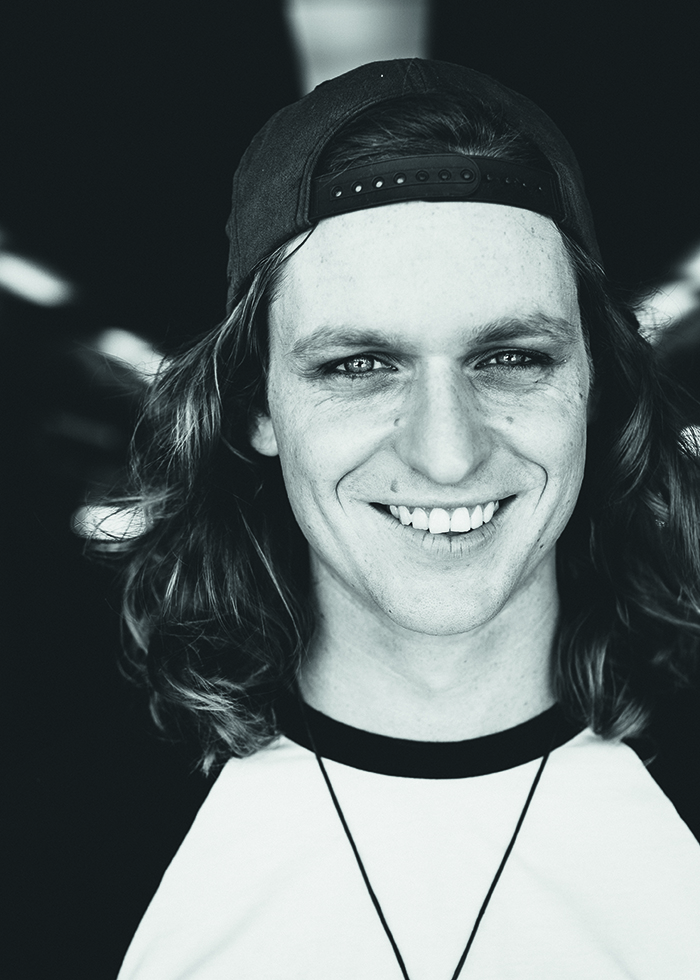

Lewis Walsh

Lewis is a likeable 24-year-old with gentle blue eyes and a steady, self-assured voice. As well as being one of Perth’s best musicians (he’s won several WA Music awards, with the Love Junkies and for his drumming), an accounting student and a part-time sign writer, he rather likes dressing up as a woman. In fact, he more than likes it. Since being reprimanded for breaking into his mum’s wardrobe and trying on her heels as a child, he’s “kind of had a whole life as a girl that no one knew about”.

“When I was seven, I stole a ballerina outfit. When I got older, I bought girls’ clothes and would wear them when my parents were out of town, basically being in girl mode for the whole time,” he says. “You have this whole inner conflict of ‘I feel like I shouldn’t be doing this – but I feel like I have to’. It becomes very confusing, and ultimately quite depressing.”

It took the erosion of a long-term relationship, and suicidal thoughts for Lewis to realise he had to come out. He had a shaking, beer-fuelled, four-hour-long admission to his bandmate Mitch, with whom he’d been close since childhood. “When I told Mitch, I remember him saying something along the lines of, ‘Ahh, that makes perfect fucking sense’, because I always had an issue growing up through high school, you know? I was always going through being depressed, plus a lot of image-based stuff. At that stage I hadn’t connected the two, I just thought I’m unhappy with the way I look, and have this weird shit happening when I get home at night when no one’s around.”

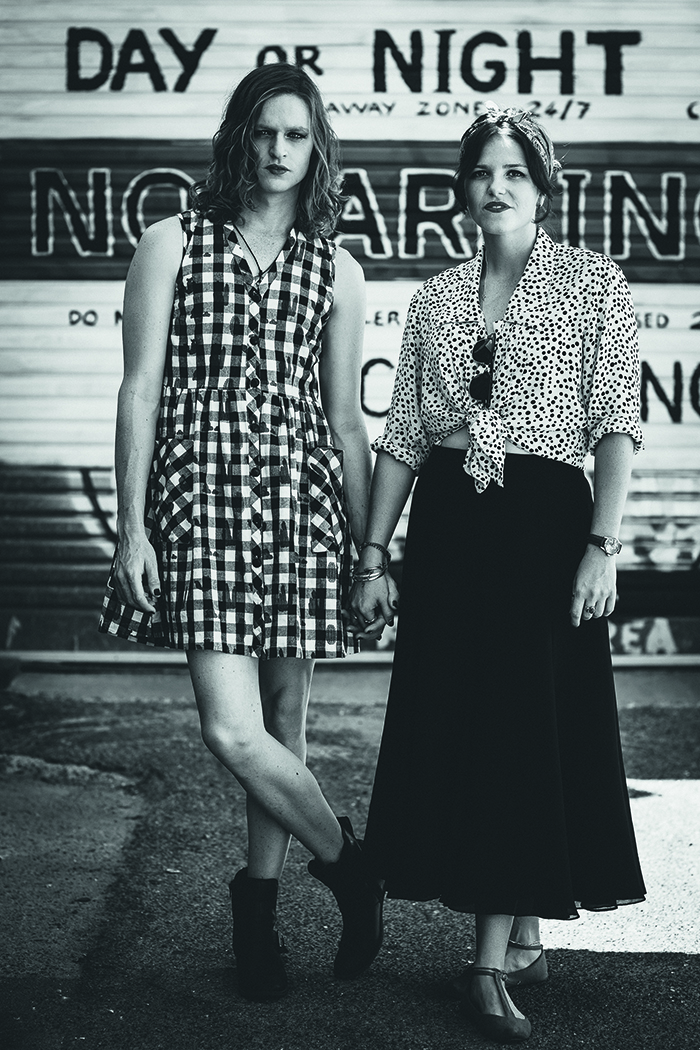

Lewis, seen here with his girlfriend Lauren, became an inspiration to trans people around the world when he told his story on a music website.

Positive responses from his bandmates gave him the courage to do the scariest thing he had ever done. “I sat my parents down, and I said, ‘I have something big to tell you,’ and I chain-smoked my way through it,” he says. “I said there’s this thing called gender dysphoria, and I have it, and I don’t know how far I want to go with it, but I know it’s there and I know I’ve always had it.”

His dad sat in dead silence until prompted by his (confused, but supportive) mother to say something. “Well… I guess I’ll look it up,” he said. Since then, thanks to the help of Google, his father has acknowledged that yes, it is a thing and, in fact, a thing he can support.

“I didn’t really have a negative reaction, so I was kind of like why the fuck didn’t I tell people sooner?” says Lewis. He barely thought twice when music site ToneDeaf asked him to pen a piece on his experience. The rest of the world did: his story quickly went viral. The outpouring of support and encouragement – on the internet of all places, where there are more trolls than under a Scandinavian bridge was nothing short of remarkable. “You are awesome,” wrote one person. “You are an amazing inspiration,” said another.

Now, he’s adjusting to living out of the closet and still figuring out where he sits on the gender spectrum. He has started to use both feminine and masculine pronouns, and is more likely to wear female clothing, even when in ‘boy mode’.

Hormone therapy is something he is considering, but not convinced by – the gender identity he embraces is more fluid. Plus, there’s the question of what his girlfriend Lauren – a drag racing car mechanic whom he met after coming out – would do if his sex organs changed. Until then, they’re keeping a sense of humour about it. A few months ago, she uploaded a photo of him to Facebook dressed in his high-vis work garb. “The mid-week transsexual is slightly less… sassy,” read the caption.

Samantha Davies

At a glance, Samantha, a 29-year-old IT worker who lives near the heart of Northbridge, is unremarkable. On the day I meet her, she is dressed in a tangerine t-shirt, rectangular specs and blue jeans; she has a certain childishness to her face, with baby-soft features and tiny teeth, but also a sharp intelligence. Immediately, Samantha starts chatting in her confident, clipped tone, lightly accented from time spent in England during her formative years – and, well, she has a lot to say.

“If you don’t have gender dysphoria, it doesn’t make any sense,” she says. “Cis people [those who do identify with their gender of birth] generally don’t notice that they have a gender, they take it for granted, so their body never feels wrong for them.” Not so for her. Born a biological male, her body always felt a strange captor. “You look in the mirror and realise that who you are is not how you’re meant to be,” she says. “You feel horrible and depressed, and it gives you anxiety. It really just tears you apart.” At the age of 12, puberty ravaged her body – her testes grew and testosterone surged, her larynx widened and her sex drive scared her with its intensity. She thought, “Oh my God, I’m different from the other girls.”

Her experience at the all-male Christ Church Grammar School – yes, the irony – was “a disaster”. Having always identified as bisexual (although she prefers the term ‘pansexual’ because, she explains, she’s been attracted to people who don’t identify with binary genders), she was ostracised for being ‘gay’. “I was always bullied, it was always ‘fag this’ and ‘fag that’ and really got me down,” she says. The teachers weren’t much help, either. “They had the attitude ‘boys will be boys’,” she trills, “which, you know, worked out really well for me!”

Samantha’s decision to come out was followed quickly by her girlfriend’s admission that she was gay. “That was convenient!” Samantha says with a laugh.

Seeking refuge in Northbridge’s Freedom Centre, a drop-in space for the LGBTI (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex) community, Samantha found like-minded people, including one friend – a biological female – who announced plans to transition. “It was like, ‘Holy shit. This is a thing! This is something that you can do’. Before that, the only representation of trans people I’d seen on television was Priscilla, Queen of the Desert – which was like the opposite of how I felt about myself.” (Rather, she’s a self-described “nerd” who likes gaming and has almost grandmotherly tendencies – “I’ve got this new Earl Grey, it’s lovely, a lot more bergamot than floral notes” .)

Her two best friends, both gay males, weren’t surprised by her admission, and – in a twist of fate just screaming to be made into a subversive rom-com – her girlfriend followed Samantha’s admission by coming out herself – as a lesbian. “Well, that was convenient!” Samantha laughs heartily.

When I ask Samantha the name she was born with, I learn I’ve made a misstep in the murky world of gender identity. “Oh, God. Oh no. Among trans people that’s considered a real no-no,” she chides me. “That’s my dead name, we don’t talk about it.”

Aram Hosie

You can tell Aram Hosie, director of research and policy at ReachOut, Australia’s leading online youth mental health service, would be great at his job – he has a cheery, relaxed nature that makes you feel it’s all going to be okay, that whatever you’re worried about isn’t so bad. It’s an approach he took to his own coming out in the workforce, a process that can be rife with anxiety for trans people.

“Just before I started taking hormones and they started leading to some obvious physical changes in me, I went and had a conversation with my manager and told him what was going to be happening,” he says. “Then my manager, CEO and I sat down and did up a little plan about how we’d inform the rest of the organisation.” Aram drafted an email telling people his plans – focusing more on the name change, communicating subtleties through the pronouns – and clicked send.

“I didn’t make it into a big deal, I just said this is what’s happening and if you have any questions, feel free to talk to me. People took their cues from it. I think if you over-engineer it, people will think it’s a bigger deal than it is.”

As well as messages of support, he received a few questions (the most common: ‘Which bathroom will you use?’). “You kind of end up becoming a talking education program,” he admits. “Sometimes it gets a little bit boring, but on the other hand, I kind of think humans won’t change, at an individual level or a societal level, unless people know more.”

He cautions transitioning people not to get bogged down in the discourse. “You can spend so much time thinking about yourself and your identity – am I presenting as male or female? I think people can get quite wound-up about people using the right pronoun, and my biggest advice is: don’t,” he says. “It stresses you out and it stresses everybody else out. There comes a point where [the name and pronoun choice] changes over, where you don’t look like or sound like how you did, so it doesn’t make any sense to call you by the old one. Just be patient and let it happen.”

Interestingly, some of the only negative reactions Aram experienced came from the lesbian community with which he was closely involved before he transitioned.

“Some, the ones who were more fifty-plus, saw it as almost a betrayal to the sisterhood to become a man, like joining the patriarchy. It’s been interesting for me to explore how I can still be a feminist as a man. I’m finding that I can almost be more effective in some of my arguments around feminism as a man talking to other men, because in my experience, as a woman talking about feminism men will sometimes dismiss you. You have a bit of awareness, like now that I have male privilege, what am I going to do about it?”

Glossary

- Gender Dysphoria – A state of persistent distress with one’s birth gender.

- Transgender – A person whose gender identity is different from their assigned birth gender.

- Transsexual – A person who does not identify with birth gender, and undertakes medical and surgical changes to move towards the gender they identify with. There is some contention with this word, and some argue it’s no longer relevant.

- F2M – A biologically born female who transitions to male.

- M2F – A biologically born male who transitions to female.

- Transvestite – A person who identifies with their birth gender, but routinely wears the clothes of the opposite sex.

- Assigned gender – Your gender as defined by your sex.

- Cisgender – Basically not transgender. Someone who identifies as the gender they were born.

- Androgynous Someone who presents as in-between genders, that’s to say both or neither. May not identify as transgender.

- Bi gender – Identifies as both genders.

- Gender Questioning – Unsure of their internal gender.

- Gender-fluid I- dentifies as both/in between/neither. Someone who feels they move between genders or is in between.