When it comes to helping young people who are suffering from mental health issues, local charity Youth Focus believes that everyone has a role to play.

The night before an interview for a fulltime job as a receptionist, 15-year-old Caitlin finally called her mum. For six months, she'd been living with her dad, a devout Jehovah's Witness, and had been instructed by the church to pull out of school and start working. "At 1am, I broke down, and called mum and told her I couldn't do it, I was so scared, and I didn't know why I was doing it," she says.

Caitlin returned to her mum's house and resumed school. "Nothing really changed," she says. "I just stayed depressed all the time. I failed school, I had really bad concentration problems. I wagged school a lot, but it wasn't to hang out with friends – I just sat at home and did nothing, and cried all the time." She struggled through two more years of school before pulling out, around the time her doctor referred her to Youth Focus, a not-for-profit that's working to stop youth suicide. It wasn't the first time Caitlin had seen someone about mental health issues. This was, however, the first time it actually helped.

"Usually I'd be reluctant to go, but they made it so welcoming and friendly," Caitlin says. "I learnt how to stand up for myself and how to set goals, and how to have a more positive mindframe. They taught me how to teach myself how to be better."

Youth Focus offers counselling to clients, as well as providing other avenues for engagement, like role modelling and being paired with a mentor for social activities. Caitlin arrived as a 17-year-old suffering from issues relating to depression, anxiety, paranoia and self-harm, and spent a year receiving both individual counselling and family counselling, which Youth Focus offers in recognition of the value of family in an individual's recovery from mental illness.

"Families are an under-utilised resource," says Coleen Van Wyk, a senior psychologist who provides support and development to Youth Focus's clinical staff. "People don't come to us in isolation, so it's about helping in all the layers around them – including everyone involved with the young person."

Before receiving family therapy, Caitlin had her mum attend one of her counselling sessions with her, to try to explore the reasons behind why Caitlin felt neglected and isolated. It didn't go well. "She was so angry," Caitlin says. "She thought everyone was telling her she was a bad parent, and walked out."

Coleen sees that a lot in the feedback she gets from her clinicians. "There are conversations that aren't taking place because of the shame and stigma in the world of suicide prevention. A lot of people, including parents, worry about judgment and blame." She says the family inclusiveness program can give a sense of what caregivers are struggling with, and how Youth Focus can support them, in order to provide holistic treatment for the young person.

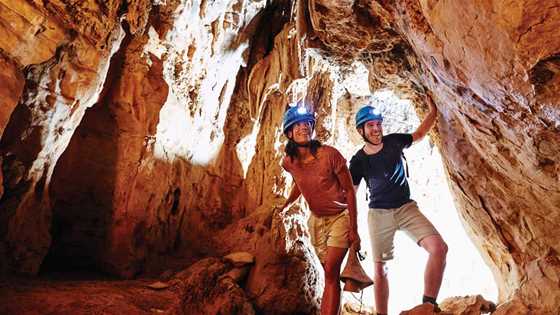

The riders at the Youth Focus Ride for Youth, one of the charity's biggest events each year.

It's something that worked for Caitlin's mum, who felt like she was being listened to. "I've never seen her so calm," says Caitlin. "We learned how to listen to each other."

That approach makes sense to Felicitie Black, the general manager of operations at Youth Focus. She oversees all Youth Focus's clinical service programs, and admits it has its challenges. "Family therapists need to be very well qualified," she says. "It's complex to hold everyone's interests in mind when you're working with a family. We're doing a development program with a consultant now to upskill all our staff, and we're sponsoring some of our counselling staff to move into that area." Further limiting the availability of specialists is the fact that Youth Focus looks for local clinicians to staff its regional offices, to ensure the therapists remain in their roles long-term. "We don't have family therapists in Albany or Geraldton, because they're fairly new offices," Felicitie says. Filling those positions is on the cards, as is expanding the family inclusion program. "We see around 1500 or 1600 young people a year," Felicitie says, and estimates that, right now, about 20 per cent of those people are seeing family therapists. It's a figure Youth Focus would like to increase. "Ideally we'd like to see that many families as well."

Coleen says family therapy goes to the core of how people are wired. "Human beings are relational," she says. "There's a belief a sign of healthy psychological functioning is to be all self-reliant and able to do things on your own and be independent, but I think it's a misnomer. For me, when I look at psychological functioning and healthy functioning, it's that ability to be independent and to have a sense of mastery, but also that ability to be able to move back into your safe place and to the people in your life when you need support."

That rings true for Caitlin, who asked her mum's permission to see a psychologist as a teenager. "I thought I really needed to have help because my mum wasn't helping me," she says. "She just assumed I'd be ok without any emotional support."

.jpg)

The Ride for Youth is key in raising awareness and funds for the work the charity performs . Photography Ian Anderick.

After therapy, Caitlin has a much better relationship with her mother: although they still fight, they're able to manage it better. That's especially true thanks to the help of her stepfather, who went to the Make A Difference awards with Caitlin's mother, to watch Caitlin speak about her journey with Youth Focus. The awards, which recognise the contributions of Youth Focus's partners, are attended by the executives of partner companies, something Caitlin says was a little intimidating. "We were all wearing bright clothes, and my stepdad was in jeans, and I had pink hair, and there were all these businesspeople around," she says with a laugh. Seeing Caitlin speak, it's not surprising to hear that when she presented, she won over the crowd. "I cried because I was so happy," she says. "So many people came up to me afterwards and said, 'I can understand people because of you.' Some CEO came up to me and said, "I think I can understand what my daughter's going through. You've really helped me. I was really lost and now I know what I can say to her. I have hope for her.' I felt so honoured."

She gave the same speech at the dinner that kicked off last year's Ride for Youth fundraiser, to remind riders of their purpose for participating. Felicitie was there, and describes the passion of the riders. "You just see people pedalling their little hearts out," she says. "Not to mention all the fundraising they do before they get on the bike." She says it's important riders know why they're doing the ride, and to feel like what they're doing is making a difference – Caitlin's story serves as a reminder of the value of Youth Focus's work, but also shows her how far she's come.

"It was just so different," Caitlin says of the speech. "I couldn't stop smiling to think that, even a year before that, I'd been so messed up, and now I'm inspiring all these people. Before I even finished the speech, 200 people started clapping and crying with me. It was crazy." She adds that giving the speeches helped her build confidence – a far cry from just a few years ago, when she couldn't make a phone call, or catch a bus because she was so scared. "As nervous as I was, I thought, 'Wow, I'm actually making a difference in these people's lives'," Caitlin says. "I can say, 'This is what's going on and this is how you can make a difference.' Not just for young people but for their families as well. We should be able to speak freely about it."

It's a notion that resonates with Coleen, who says psychological recovery for young people won't happen with clinical intervention alone – it needs systemic support, too. "My role is about looking at all the people in a young person's network," she says. "How do we help those people to believe that they've got such an incredibly important role? Because we all have a role – everybody who is connected to a young person has a place and a purpose. Don't underestimate what you can do. Don't underestimate the value of a kind gesture. I talk to people day in and day out in counselling, and every time people ask me to use one word to describe what comes out, I say 'loneliness'. A sense of isolation, a sense of disconnection."

Caitlin agrees. She describes how her moods have changed as she's received treatment for her depression. "When I was at high school, I just hated it. I isolated myself from people – I was like a recluse. I was depressed all the time and I felt like I would never get better. I had no hopes for the future, didn't care what happened to me. I avoided thinking about it. But now, life is good." Caitlin's now studying psychology at uni, and mentions her boyfriend – they just celebrated their first anniversary – saying, shyly, that she's pretty happy with herself. "I feel really confident and easygoing," she says. "I never would have bleached my hair, and used to wear jumpers all the time and cover up my body. And now I feel so much more free. I had pink hair! No one in my head is restricting me."