Ted Snell is the director of the University of Western Australia’s Cultural Precinct, and currently the WA art reviewer for The Australian.

ARTIST TO WATCH

Ian Williams

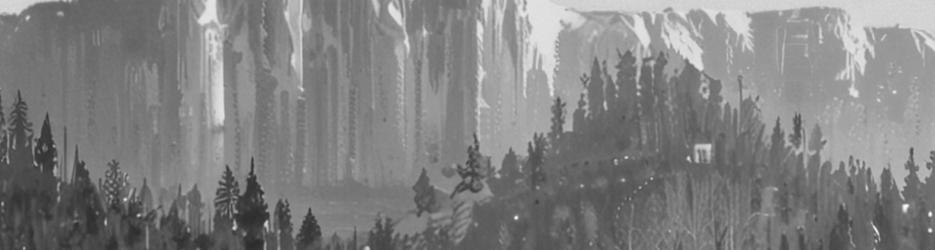

An artist's most creative act is to create his or her practice. "I have constructed my practice out of my passions," confides Ian Williams, by way of explaining how he has reconciled his commitment to making oil paintings on canvas and board, while maintaining his enthusiasm for gaming and his fascination with the digital world. Combining those two environments and exploring what are the unique properties of both has directed his works as a student and now as a professional over the past six years.

The small-scale pieces that fill his walls and are stacked neatly in racks testify to his fascination with the traditional processes of painting. Their soft tones and pristine surfaces exude restraint, yet they have a compelling quality that demands closer attention. Neatly aligned tubes of paint, containers of oil and medium, an assortment of brushes and a stack of easels are the stock in trade of any plein-air painter. But instead of gathering up his equipment on his back and setting up in some scenic patch of landscape, Williams enters the digital world, and paints in streets strafed by gunfire and patrolled by terrorists armed with bazookas. Not infrequently he is forced to retire when his avatar is mortally wounded, but he immediately returns revived and ready to continue painting.

His first Atari in the 1980s offered a creative escape for a young boy. It was a place of excitement and one that demanded great leaps of imagination to convert pixelated forms into a concrete reality. Playing in the 'real' world and the 'imaginary' world at the same time required flexibility and adaptability. Those same skills are at the core of Williams's ability to mimic/mirror/refract the digital environment in his wonderfully seductive paintings.

Photography Adam Borello.

Their surfaces may have the allure of slick professionalism, but there's nothing glib or clichéd in his translations. Just as the digital is famously seductive, so Williams embraces the tropes of Romanticism to construct enticing equivalents. Proficient in managing the technical sophistication of the medium, he works 'in the moment' to capture the instant of transition between one and the other. Through a soft blurring of the image, he situates us on that membrane between seeing and knowing, which provides new lenses that offer insights that seem to bridge the Utopian and Dystopian extremes of both worlds.

This is the "magical, sacred space of viewing" he assigns us when we stand before his paintings. It is a space for contemplation, a quiet and slow place incommensurate with the cacophony, pace and ubiquity of the digital environment. Standing before a single, still work that demands our time and attention opens a portal onto multiple possibilities of engagement. The results can be game-changing. The vastness of Cascade – shown in last year's Bankwest Prize – with its tantalisingly nuanced ambience, creates an arena for projection, speculation and deliberation.

Last year was extremely busy for Williams, with work in six shows in Perth and at MOP Projects in Sydney, so 2016 will be a time to rebuild and re-focus. Whatever transpires, he is most definitely an artist to watch.

The Perpetuate Puzzle 2015 by Jamie Worsley.?Blown and cold-worked glass?20x9cm. ?© Jamie Worsley 2015.?Photography Kevin Gordon.

LUMINOUS: TOM MALONE PRIZE 2016

Glass is the most wondrous of materials. It is an alchemist's dream, transmuting the most common of matter – sand – into transparent vessels of great delicacy and beauty. A molten blob of glass transforms from liquid to a solid through the agency of fire, to create extraordinary forms.

This most mysterious and magical of materials is celebrated each year at the Art Gallery of Western Australia, through the Tom Malone Prize. Now in its fourteenth year, the prize showcases the best work of contemporary Australian glass artists. In 2016, more than a dozen artists were short-listed for the annual acquisitive award: Ruth Allen, Andrew Baldwin, Gabriella Bisetto, Brian Corr, Mark Eliott and Jack McGrath, Kevin Gordon, Marc Leib, Jeremy Lepisto, Jessica Loughlin, Kumiko Nakajima, Kirstie Rea, Janice Vitkovsky, Zoe Woods and Jamie Worsley.

Their works have been on show at AGWA since February, and this year's winner was announced in mid-March: Gabriella Bisetto, for her work Becoming. The judges referred to the piece as "instantly, unavoidably compelling" and "brilliantly bold".

Gabriella joins a stellar cast of previous winners who are now featured in the State Art Collection, including Nick Mount, Jessica Loughlin, Clare Belfrage, Benjamin Sewell and Tom Moore. Art Gallery of Western Australia, until May 2.

Nyarrie Morgan, Newman (photography Carly Day, Martumili Artists).

REVEALED ART MARKET

The art of Aboriginal Australians is internationally acknowledged as one of the most significant movements of the last forty years. The diversity and scope of creative practice often make it difficult to encompass – for that reason, the 2016 Revealed Art Market brings together artists from 22 Aboriginal art centres from across Western Australia. It's a unique opportunity to buy works directly from emerging and established Aboriginal artists, with 100 per cent of the profits from sales returning to the makers. Now in its fifth year, Revealed offers affordable

artworks starting as low as $50, and provides a chance to meet face-to-face artists from the Kimberley, Pilbara, Mid-West, Goldfields, Western Desert, Great Southern remote and regional centres. Fremantle Arts Centre, until May 22.

Photography Tim Lofthouse.

ART INSIDER

Stephen Bevis believes his role as arts editor for The West Australian is to constantly remind his readers how close to the arts they are. In their personal lives, through their networks and in their daily environment, they meet artists and engage in arts events, sometimes without realising it. For this reason, it's necessary to abandon the "… ghetto mentality and place the arts in general news," he says. Perth's cultural life is booming, and keeping a focus on the arts as part of the everyday experience of all Western Australians is one of the best ways to reinforce the vibrancy of the local arts scene.

His undergraduate degree from the University of Western Australia was in Literature, studying under Writing WA chair Dennis Haskell, and while that experience has shaped his broad interest in the arts, he insists he is more of an outsider than an insider. Neither a practitioner nor hailing from within the arts milieu, he sees himself as an interpreter or interlocutor, creating a bridge that provides opens access to what can seem like a secure and secret enclave. All disciplines have their jargon and argot, to prevent outsiders from entering into the inner circle of understanding, so asking the right questions and presenting the answers in clear and accountable terms is the vital role that journalism plays in the ecology of the arts. After many years of bedazzlement when confronted with 'artspeak', Stephen thinks he's learned how to ask the dumb questions, and get away with it.

In a competitive offering of news and comment, The West Australian retains its draw-card role because it remains the journal of record for what is happening in the arts. Despite the decline in the fortunes of print media, The West's art coverage under Stephen's leadership maintains a high profile. While he agrees newspapers are by their nature reactive, he points to The Giants event last year and the significant role The West played in swaying potential supporters, and then in delivering a massive audience. Of course, The West Australian's sister enterprise, Channel 7, had taken a commercial interest, which was an added incentive, but these two arms of the Kerry Stokes media empire were able to work in tandem to promote a cultural event that re-activated the City of Perth. In a similar way, The West assists in delivering huge annual audiences to Sculpture by the Sea on Cottesloe Beach.

With an audience that is increasingly time-poor, habituated, and searching for novelty, it's important to find new ways of showcasing arts events. He points to the Rijksmuseum's flash mob event in which Rembrandt's masterpiece The Night Watch was recreated by characters in a shopping centre in Breda, to re-awaken interest in visiting the original work at the newly refurbished museum. "The arts are often captive to their institutions and the bureaucracy that surrounds them," he says, and it's important to break out of that mould and find new ways to connect with audiences. His challenge in this changing environment is "honouring the interests of the audience, as well as honouring the ambitions of the artists". It's a balancing act for all involved, requiring sensitivity, skill and subtlety, but it's vitally important to ensure the best outcome for all.

I am my Mother's Son 2015 by Jacobus Capone. Photograph installation at the Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery, HERE&NOW15.

EMPATHY

As a species, our capacity to understand or simply show respect for another's condition is the trait that distinguishes us from apes. Renowned anthropologist Sarah Blaffer Hrdy explains that "… our aptitude for imagining the emotions

of other individuals is a powerful indicator of our humanity," and author Ian McEwan goes one step further by suggesting that human beings can only inflict suffering if they are without empathy for others, because "cruelty is a failure of the human imagination".

This may account for our attraction to artworks that stand witness to that spark of revelation leading to deep knowingness. It is at that moment when we share our sense of humanity and express that most characteristic of human emotions, empathy. This quality is discernable in the works of Colin McCahon and Howard Taylor, in some of Bill Viola's videos, in the works of Lynette Wallworth, and also in the photographs, performances and videos of Perth-based artist Jacobus Capone.

Wallworth orchestrates this empathetic connection with deft and economical skill. In the haunting Evolution of Fearlessness, commissioned by the New Crowned Hope Festival in Austria in 2006, Wallworth filmed eleven women, most of whom were political refugees. In the work, they gradually appear as if beckoned by our touch on the screen, and raise their right hand in a gesture of fearlessness and trust while silently communicating their story of suffering and endurance. Their bodies eloquently reflect their story, and we stand witness as one after another moves forward from the darkness. Each has an extraordinary story of surviving war, concentration camps, torture and extreme acts of violence, which are detailed in an accompanying volume, but without that specific knowledge, the understanding of their suffering is immediate and so intense it transcends the gallery space.

"The contemplative state is, in fact, the ideal state in which one loses track of time," Wallworth explains, and it is exactly that sense of being 'out of time' that gives her work its extraordinary resonance. It is impossible not to feel transported, to lose connection with the routine of living, when confronted with such raw but restrained emotion.

The poetry of Jacobus Capone's works lies not only in the beauty and simplicity of their presentation but in the access they provide to understanding that seems beyond us in our everyday circumstance. This comprehension is revealed by Capone through a process of unknowing and unlearning, in order to recover a clearer relationship to objects in the world. For his recent work I am my Mother's Son, shown at the Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery in HERE&NOW15, he and his mother both wore radio stethoscopes for the nine weeks of the show, broadcasting their heartbeats into a silent, dark space in the gallery. In that space, we aligned our life's force with theirs in an act of private communion.

Great art has always had that capacity to move us, to shift our thinking and dig deep into our souls. It is most effective, however when the timeless space becomes charged with possibility and purpose. We emerge from our engagement with these works, if not reborn, then, at least, more self-aware, more empathetic, and more attuned to our intimate and extended worlds.