Bremer Bay isn’t just a hotspot for thousands of New Years Eve student revellers. In a deep-sea canyon 60km offshore, there’s a different party to enjoy, and its guests of honour sit at the top of the oceanic food chain – the orca, or killer whales.

It's early morning, one Sunday in March, when Naturaliste Charters' Cetacean Explorer arrives at the dock of the tiny Bremer Bay harbour.

"Nice and warm?" the captain, Mal, shouts down at the crowd of 30 passengers who've been waiting in the rain. We watch as the barefoot crew load up the boat

and banter about their Saturday night at the local pub, the Bremer Bay Resort,

where I too had tucked into a hearty pre-cruise meal.

At last we're invited to walk up the plank and take comfortable, dry seats in the cabin. We lurch into the 90-minute journey out to the canyon, and I heed Mal's advice to pop a seasickness tablet, just in case.

He introduces Leila and Bec – the resident marine scientists from Curtin University – who brief us on the cruise's star attractions.

Blessed with a serious set of chompers, the orca, or killer whale is actually the largest member of the dolphin family, and not a whale. Despite being endangered, the orca is the most cosmopolitan marine mammal species, found in all the oceans of the world. Highly social, they travel in family groups, and larger combined pods. Naturaliste Charters has seen in excess of 100 killer whales at the Bremer Bay Canyon site.

Not much is known about the Australian orca population yet, Leila explains. Each day she photographs nicks and curves on their fins to track and monitor their behaviour – male orcas, she says, have larger triangular fins, and females have curved fins. Males can live to 60 years old, outlived by female orcas by up to 30 years. In fact, a 'Granny' from the northern hemisphere is reported to be about 103 years old, says Bec.

Marine scientists Leila (left) and Bec lead the effort to spot the orcas.

Granny orcas rule the pod. At up to 7.7m long and weighing six tonnes, the gigantic females are smaller than their 9.8m-long, 10 tonne male counterparts, but orcas live in a matrilineal society, often staying with their mothers and grandmothers for life.

The scientists conclude their briefing, and when the boat starts to slow, I head upstairs to look for these fascinating creatures. Mal, who is a marine biologist as well, tells us to keep an eye out for a cloud of mist – the blow – which will hang in the air for four seconds before dissolving.

I know orcas are an 'apex predator', so ask Mal what they eat.

"Everything" he replies. "Squid, most fish, turtles, birds, other whales..."

"What?"

He tells me that, last year, the crew watched as a group of orcas preyed upon

a beaked whale, a rarely seen species that lives in the deepest depths of the ocean.

After echolocating their prey from up to 500m away, orcas employ clever teamwork, such as beaching themselves to scare seals or penguins into the water where more killer whales are waiting to feed.

"Do they eat sharks?" I ask.

"If they're dead."

And humans?

"They can scan your skeletal structure with their sonar," he says, "but they reject land-dwelling vertebrae."

I am not the first to feel a peculiar blend of horror and awe toward this ancient species. Mal informs us that the Latin 'orca' translates to 'belonging to

Orcus, god of the netherworld'.

The sun is coming out now, and Mal squints against the glint on the water. I think I see an arcing back, but it's a shadow.

Mal, the captain of the Cetacean Explorer.

Bec and Leila are regaling the fascinated guests with stories of their worldwide research expeditions. "I've worked with bottlenose dolphins, Chinese white dolphins, sperm whales, humpbacks," says Bec.

Mal scolds the scientists: "The two most experienced eyes on the boat and

you're talking…"

Leila takes up her binoculars, and gets back to her task as we look on in anticipation. She soon spots something on the horizon. As we move closer, puffs of mist and tiny black triangles materialise above the waves.

The scientists call out directions – "Three animals, 90 degrees!"; "Yep, five animals, 200 degrees!" – and slowly but surely, we pull up toward the orcas.

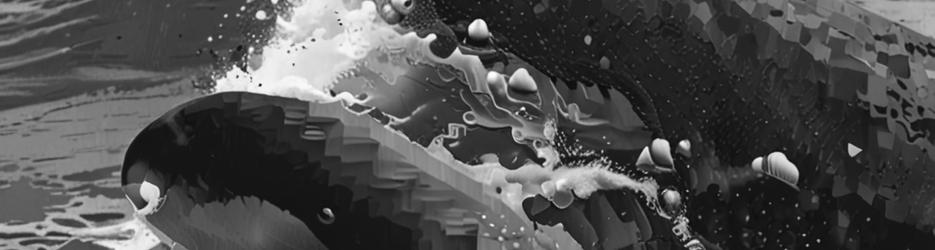

An onyx back curves, glistening, weightless, from the water a stone's throw away. We're getting closer.

Riveted, we crowd onto the bow. A pair of killer whales rise up on the port side, another to starboard, several dead ahead. They're huge. I try in vain to capture them on my camera when, suddenly, an enormous black-and-white mass appears under the water right beside the boat. Mottled and gliding below the aquamarine, it turns on its side to look up at us with a black-rimmed eye, then arcs out of the waves at my feet. I gasp, stunned, at its enormous black-and-white head, grateful my bones are unpalatable.

The orcas rise from the water in rows. The crew recognise some of the pod, but normally shy bulls are also surfacing, and mothers with calves. The scientists squeal with delight.

For hours we follow them, transfixed, inching closer and closer so we're eye to eye. But when the orcas want to move, they move like lightning, at 50kph, leaving us staring into the royal-blue bay.

As we drift across the canyon I call them back with my mind – perhaps their sonar can read that as well. Lunch is served, so I go downstairs for a snack... and, suddenly, outside the window, a pair of bulls swing up before my eyes and dive underneath the boat. They heard me!

It's like being in a nature documentary – Esperance filmmaker and naturalist David Riggs's next film, to be precise, which is being shot on the cruise and is scheduled for release on the Discovery Channel in July.

Riggs began studying the remote marine wilderness in 2005, detecting an unusual abundance of Bluefin tuna. Soon he was spotting sea birds, sunfish, giant squid, several species of sharks, and sperm whales. He also found the canyon was home to the largest pod of orcas in the southern hemisphere.

.jpg)

The canyon is home to the largest pod of orcas in the southern hemisphere.

With the 2013 release of his terrifying documentary Search for the Ocean's Super Predator, Riggs identified the area known as Bremer Canyon as a marine-life 'hotspot'. He speculates that deep inside the canyon, a fertile fuel deposit leaks an ice-like reef of methane hydrate. Crustaceans form their homes there, releasing billions of nutrient-rich eggs, and the circle of life begins. In 2014, Riggs and Naturaliste Charters began running killer-whale cruises, a joint venture that took off, drawing thousands to South Western Australia and remote Bremer Bay.

An underwater camera is thrown down over a frolicking pair of newborn calves. At two metres long, they look more like their friendly dolphin cousins. Yellow patches show that these calves are just a few weeks old, meaning they can't have been born too far away, says Leila.

Bec lowers a microphone over the side. She is doing a PhD on the acoustics of killer whales and is the first person to study them in Australian waters.

"Orca have three types of vocalisation," she explains. "Whistles, burst pulse sounds, and echolocation."

Bec says that orca pods around the world have different 'languages'. "I'm categorising the call repertoire of these orcas, and I'm interested to see if there is geographic variation and potential for different dialects in populations."

An albatross casually observes the bobbing microphone rope. On the boat, we hear nothing. "They're not talking today," Bec says, and pulls the mic up.

We cruise back across the canyon, still gazing out at the water for fins, but seeing only shadows.

"It's gone quiet," Mal confirms, and soon everyone is sprawled out in the sun and nodding off as we speed back toward the Bremer Bay coastline. I sit on the bow, enjoying the sensation of flying across the glossy waves into the sun and the wind.

And that night, as I fall asleep to the thundering chorus of the ocean crashing against the cliffs below Villa Varuna, I find I can still see those rows of misty puffs – five or six clouds appearing in a neat line like magician's smoke – then the slick fins, the gigantic black backs rolling shining into the sunlight before diving away in a slow, archaic rhythm, mysterious and intense.

BREMER BAY

It's impossible to feel stressed in Bremer Bay. From the outskirts of Perth, it's

a five-hour drive south through peaceful golden farmland, and 180km east of Albany. It's off the beaten track all right, and a slice of southwest coastal paradise. Not only is Bremer stunning, and packed with unique wildlife on

land and sea, all the local characters living in this charming, eco-friendly spot seem larger than life, too.

NATURALISTE CHARTERS

Daily expeditions to the Bremer Marine Sanctuary will run from January through to April 2016, allowing you to experience this awe-inspiring phenomenon and at the same time support the Bremer Canyon Killer Whale research project. Visit whales-australia.com.au/bremer-killer-whales.

ACCOMODATION

For short-term lettings in Bremer, contact Deb La Rosa at Bremer Bay Accommodation. I stayed at the luxurious Varuna, a loft-style villa peppered with Italian antiques and Persian carpets, with impossibly high timber-beamed ceilings and floor-to-ceiling windows that drink in the sweeping horseshoe arc of the bay

and the wildly beautiful Dillon Beach. The stunning Varuna is for sale (I wish!). Visit bremerbayaccommodation.com.au.

The highly rated Bremer Bay B&B is also on Deb's list. Be sure to book in for heartfelt family service, and breakfast of fresh-laid eggs, homegrown tomatoes, bacon, toast and tea at the gorgeous homestead of Jeni and Drew, their two adorable sons and their guard dog, Scrappy. Visit bremerbaybedandbreakfast.com.au.